*

Miguel Ángel Hernández-Navarro, University of Murcia, Spain

Dwelling time

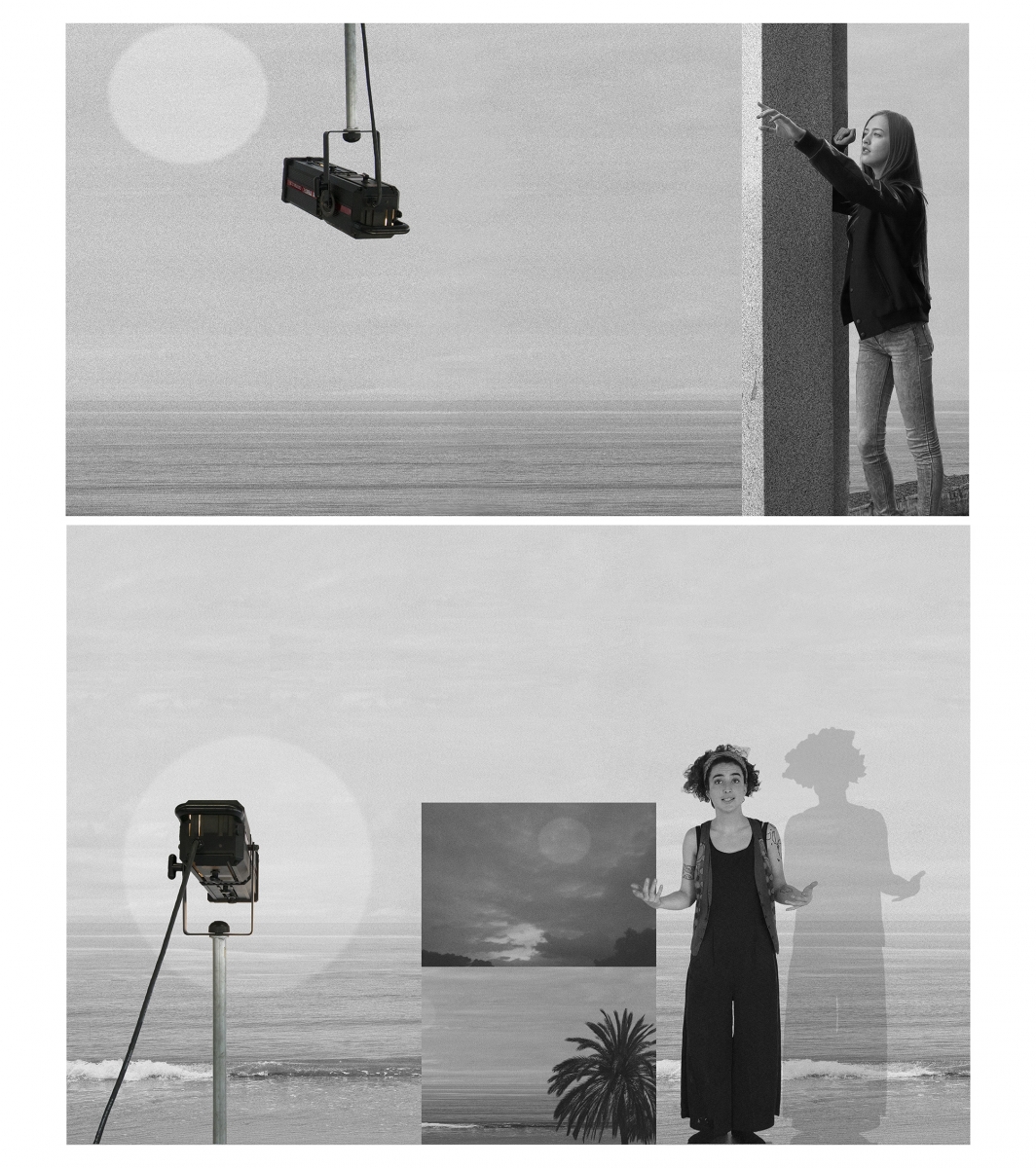

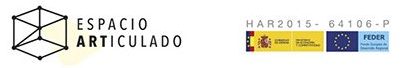

In Point Omega Don DeLillo (2010) describes the experience of a visitor who is in a gallery in front of 24 Hour Psycho (1993), the work of Douglas Gordon that is a twenty-four hour slowdown of the famous Alfred Hitchcock film. In the room, protected by the darkness and bathed by the light of the images, the protagonist of the novel of DeLillo has the sensation of inhabiting a different time and facing an alternative mode of perception to that of normal daily life. For the character, as for anyone who has experienced Gordon’s installation, time slows down; it almost seems to stop, even if it never stops completely. The work provokes an opening in time of the cinematographic image. It makes us aware of the interstices between one plane and another, shows us that this apparent continuity of the image-movement is indeed only apparent, and invites us, ultimately, to look into the interstices, the ellipses between frame and frame, in those places that do not take place when the image develops at its usual speed of 24 frames per second. Gordon then opens the image. He opens it, but not completely. It is not offered as something static, as a fixed-image, but as an image that is halfway between the fixed-image and the image-movement, an image that is, as the protagonist of DeLillo’s novel says, “pure cinema, pure time”.

For DeLillo’s character the images end up producing an awareness of time, a temporary experience in which, in the end, “one is aware that he is alive”. It is the feeling of living a different time, another time, away from the rumor of the street. A time that is not, however, the time stopped, eternal and quiet, which is usually the time of artistic space. It is not a time without time –and this is what most seems to interest DeLillo– but rather of another time. A time that moves at a speed for which we are not ready. Because it never stops completely, so there is no possibility of total pacing. Time is never there, as we wish it were. And in that way, paradoxically, we are aware of it.

Gordon’s work is an opening of time, but also an opening of technology. He opens the filmic image as one opens a toy. He dismantles it, hacks it, and profanes it or, as Nicolas Bourriaud has suggested, he postproduces it (2004). A postproduction that causes the artist to appropriate the images and give them a new meaning which, however, does not completely erase the original sense, but perverts, disassembles, cracks and makes it evident. To open the image is to open the time. And opening the time is, without doubt, spatializing it, creating a gap, a place to inhabit it.

Ultimately, what interests Gordon is producing a temporal self-conscious experience, an experience that leads us to an alternative time. The image as a counter-time, a time against it, against modern time. Against the standardized time that Sylviane Agacinski called “Western time” (2003), and that is nothing but time for work, progress, machinery, the time over which the subject has already lost any chance of sovereignty. It is the accelerated time that arises from the experience of modernity. The famous scene in Modern Times, in which Chaplin, exhausted by the assembly line, starts putting screws in all the objects around him, serves as a perfect metaphor –perhaps somewhat exaggerated, yet it is true–: the modern subject “extends” the machine rhythm to everyday life, internalizing and endorsing the times of the production line.

Undoubtedly, the birth of the modern subject was linked to the “subjection” of a time that, increasingly, was no longer his time, but a simple time, the time of succession and the accelerated repetition of the same action. In a way, it could be said that modernity established the unique time of production and technology –the only vestige nowadays of the belief in progress– the time of continuity and speed, or, as Mary Ann Doane has suggested, cinematic time, (2002) characterized by the ellipsis and the suppression of the downtimes, those times which are precisely the times of the human, those who escape the light of the spectacle, the times of the shadow. It is the rhythm of production, which eliminates all that does not serve: affects, emotions and desires, everything that cannot be easily absorbed and marketed. Authors like Paul Virilio (2006) or Hartmut Rosa (2013) have theorized that mechanization, acceleration and progressive disappearance of time that characterizes our era.

If we think about it right, in the face of that capitalized, transparent and accelerated time, the time of Gordon’s work proposes a tangible time, a time that the subject can almost grasp with his hands. It is pure duration, beyond the time of the clocks, beyond artificial time, a time almost material, dense, dilated, in which it is possible to inhabit, a room-time, a room of time.

24 Hour Psycho is one of many examples we could bring up of the interest in the question of temporality shown in recent years in contemporary art. This distortion of time and awareness of temporal experience has become one of the central places of art of recent decades, particularly –but not exclusively–, in what has been called the time-based art, the art of Image-time. Suspended works of art, that are floating, slow-motion, fast-moving… denaturalized movements, repetitions, interruptions, temporary jumps, discontinuities, anachronisms, asynchronies, desynchronizations… Through a variety of strategies and disciplines, a large number of contemporary artists have begun to question the hegemonic temporality of the present, disfiguring and re-elaborating the experience of that linear, standardized and “monochronic” time of modernity.

Of course, the presence of time in contemporary art practices is not only reduced to this denaturalization, perversion or desecration of the movement of images, but has become fundamental to many other levels. These same resistances to the established time are central, for example, in the artistic work around the discourses of memory and history, that puts in play a sense of time like something open and manipulable, where present and past are connected and in constant movement.

Such a revision of hegemonic chronologies through the images corresponds with the emergence of a whole series of historiographical and methodological proposals –such as the anachronistic story of Georges Didi-Huberman (2005) or preposterous history of Mieke Bal, (1999) to name but a few examples– These propose models of analysis of the images characterized by the introduction of multiple temporal levels that are projected through the history. As Keith Moxey (2013) has suggested, such temporal multiplicity takes on an essential role in the scenario of contemporary global art, where various temporal lines coming from different contexts of the globe converge in an antagonistic and conflictual way in what we call the “contemporary world”. In this way, any attempt at writing about the art of the present needs to rethink the concept of time and assess both the temporal multiplicity –heterochrony– and the inversion of time and history –anachronism–.

Whatever it is, what is clear is that a brief look at the contemporary art of the last decades will find a whole series of poetics that have time as a center of reflection. In all cases –and this is what is important– the dimension of time is used as a weapon of resistance against the established, against the hegemonic regimes of temporality, resisting time through the introduction of another time; a denaturalized time, a profaned time, life time, subjective time, duration time, time of the past, memory time, times that alter the temporary model instituted by modernity.

What I would like to do in this short essay is to look through some of these ways in which art faces its historical time. The thesis that I intend to show is very simple and is stated from the beginning: artists propose counter-times, different times, alternative temporalities that dismantle and question the temporal hegemonic regime of the present.

In search of lost time

At present it seems clear that it is not possible to speak of visual art without introducing the question of time. How can we speak of sculpture or painting, for example, without alluding to the perceptive experience, to the stopped narration, to the times of reading the image? And that still seems more evident when we allude to the art of the avant-gardes, whose reflection on time was present on all levels: from the multiperspective of cubism to the speed of the futurists, passing through the psychic time of surrealism –remember the clocks of Dalí. It seems appropriate that time is a central component of visual arts. However, for many decades, time was expelled from visual art. Modernism, the hegemonic reading of 20th-century art that shaped modes of seeing, experience, production and exhibition of art, tried by all means to abolish time. Based on the famous division established by Lessing between arts of space and arts of time, critics like Clement Greenberg (1961) –during the forties and fifties– or Michael Fried (1998) –throughout the sixties– built a sense of modernity linked to the medium specificity: time was typical of music or literature but visual art, however, developed in space, without time. From these premises, Greenberg and Fried, conceived models of aesthetic experience centered on the elimination of time. These models valued that the experience that the painting or sculpture could provide should be purely visual, established through a kind of –presentness– far from the time of life. For that reason, among other things, they advocated an abstract art, beyond narration, politics, reading time, beyond time… of life, an autonomous, pure art, which turned the artistic into something close to sacred. The work of Pollock in painting, or that of David Smith in sculpture was for Greenberg the culmination of that process of elimination of time, which for him had begun much earlier, with Manet, in the beginnings of modern art.

Despite its institutional pre-eminence, since the late 1950s, this model of vision began to be questioned by artists, theorists and critics. In her famous Passages in modern sculpture, published in 1977, Rosalind Krauss (1977) showed how the discourse on modern art, particularly on sculpture, was created through the elimination of time, and made clear that a history of modern sculpture –of modern art in general– could not be carried out without introducing the temporal dimension. A fundamental dimension since the beginning of modernity and even more at that time, with the entry into the artistic realm of a number of essentially temporary new practices and disciplines that highlighted the artificiality and fiction of the modernist conception of art. These arts of time were essentially video, film, photography or performance, those disciplines that, in one way or another, claimed time as a critical category. Thus, time began to become a central concern for artists and critics after a period characterized by an absolute “chronofobia”, –to say it in words of Pamela Lee (2004). From that moment a kind of recovery of the lost time took place that acquired the most diverse forms and strategies.

Working with duration and experience of time frames was essential, for example, in Neo-Dadaism and the development of performance art from the famous piece 4’33’’ (1951) of John Cage, where time marked the duration of the piece, to the One Year perfomances (1978-1986) of Tehching Hsieh, characterized by performing radical actions for a specified time, in this case, a year. And along with this preoccupation with time as a delimiter of action, a large number of artists began to be interested in another question that had been out of the reach of modernism: the process, the phenomenology of doing, everything that was before the work of art was almost magically situated in the gallery –the only place that interested the modernist critic. Artists like Robert Morris and Robert Smithson exposed the importance of the temporality of the work of art before it was finished, or even beyond, making it clear that there was no work of art at the end, but the work of art was the process itself. As in Morris’s Continuous Project Altered Daily (1969), where the concept of a finished work of art is called into question by the continuous alteration of the work during the weeks that the exhibition lasted.

It was about introducing real time into the work of art. And that same introduction of natural time was essential in the temporal reflections that the Land Art inaugurated, directed from the beginning by an attempt to align and conjugate temporalities belonging to different scopes and contexts: geological time, astral time, human time, cultural and affective time. Smithson’s work of art is a clear example of all this. A problem that is also contemporary to certain artistic writings of the moment, especially visible in the writings of George Kubler (2008), which affected and influenced a generation of artists during the sixties.

Reflecting on perceptual time was another way to make up for the lost time. From minimalism, artists were aware that the work of art could not be experienced at a glance, a quick look that happened in that presentness as modernists claimed, but it was necessary to experience it temporarily in space, both through the body as through the mind. The work was read, interpreted, there was a temporal process in the artistic experience that began to be of relevance. The spectator, in this way, also recovered the time that had been taken from him.

Finally, one could say that temporality was central to many other artists who, from conceptual art, reflected on subjectivity and identity. Perhaps the clearest example of this is the work of art of On Kawara, both his Date paintings, paintings marking the day of its production, as in his telegrams and postcards made as temporary markers of existence, or especially his books One Million years past and One million years future, that are written a million years into the past and into the future and make visible, at least in their linguistic meaning, the metaphor of “a long, long time” or “A very, very far future”. Time becomes a present and unavoidable dimension.

These would be some of the countless examples of working with time during the 1960s and 1970s, a period, in which, the dimension of time was once again crucial to understanding the artistic experience. As was also the case with language, body or politics, according to Martin Jay (1999), in short, it was life, which had been expelled from art by the modernists and which now returned with recovered intensity. Thus, as Hal Foster (1996) has argued, the neoavant-garde art of the sixties and seventies activated the culmination of one of the central aims of the historical avant-gardes and all modern art from its beginnings: the disruption of the boundaries between art and life.

Denatured time, open time, affective time

After the recovery of time, this dimension was no longer separated from art, nor critical reflection. And little by little it has become a category whose use serves to show the resistances of a work to certain central ideas of modernity. Facing acceleration, monochronic or capitalized time, the temporary experiences provided by art have begun to be seen as an alternative way of temporal experience, as a mode of resistance to the hegemonic time of the present. This critical capacity of time and above all its centrality in the historical-artistic debate has reached its climax in recent years, where it has become, as I mentioned at the outset, a problem and an open question and treated in various ways. Christine Ross’s recent book (2012) is an example of this emergence of time within today’s artistic discourse. It describes a mapping of strategies, practices and problems which I could barely list here.

I began this text by alluding to one of the most obvious issues, the alteration of temporal rhythms in Douglas Gordon’s work. His work, like that of many others, such as Stan Douglas, Jesús Segura, Eija-Liisa Ahtila, James Coleman or Dough Aitken, breaches the consumption and capitalization logics increasingly present in the current world of contemporary art through alteration and manipulation of the technologies of the image, that accelerate, interrupt, denaturalize and upset the daily temporal rhythms to produce perturbations in the perception of the images.

Another of the centers of tension in the uses of time in contemporary art is the relation between past, present and future. The discourses on memory and history bring into play a sense of time as something open and manipulable where past, present and future are connected and in constant process of construction. This happens, for example, in the works of art of Tacita Dean, Matthew Buckingham, Francis Alÿs or Rosell Meseguer, artists who, through archive, montage, historical performance or anachronism, rewrite history and bring the past into the present. I have carefully analyzed these practices in Materializar el pasado: el artista como historiador (benjaminiano) (Hernández-Navarro, 2012). There I was trying to show how a large number of current artists work as historians, understanding history in a similar way to that deployed by Walter Benjamin in the thirties of the last century –also in an era of change, crisis and dangers–, with history as something latent and alive, which affects the present and is the key to building a future. The time opens up, and the past and the future communicate. In this sense, the crisis in linear time and the advance of time in one direction, forward, are also called into question. These artists seek the hope of change in the past, rather than in utopia, identifying what might have been, the future that inhabited the past, unfulfilled possibilities. It is a work with latent energies, frustrated dreams, utopias of the past, and a kind of archaeology of the future that never happened. The artist acts as a connector of times, as an assembler of different temporal regimes who, by montage and collision, activates possibilities of experience that had not yet been completed.

Another fundamental way of working with time in the present is what, in the face of capitalized time, we could call “affective temporality”. Confronting the machinability of the temporary experience and the idea pointed out by Antonio Negri (2006) that the rhythms of the assembly line and the factory have possessed the modern experience, and that our time has been turned into pure capital, many artists show the temporality through the affects. Consider the synchronized clocks of Perfect Lovers (1987), of Félix González-Torres, that mark the time of love, illness and loss; the emotional chronologies Now, Elsewhere (2009), of Raqs Media Collective; or even the subjective timing of One Year Celebration (2003), of the Association des temps libérés, created by Pierre Huyghe to assess downtime beyond work time. In all cases, time becomes emotional, it becomes pure emotional duration, beyond the rhythms of capital.

Counter-chronologies of contemporary art

Ultimately, one could say that all these reflections on temporality are at the center of the debate about the global world and the times of history. And it happens that one of the consequences of globalization in the field of humanities has been the crisis of historical discourses centered in the West and the linear conception of time. From history, art and philosophy it has been shown –think of the case of Walter Mignolo (2012) among others– how the linear, causal and teleological universal history sense has been disarmed and historical times have begun to be thought of as a multiplicity of lines, traditions and temporary experiences that no longer have a single center or a single direction.

Authors such as Terry Smith (2010) have referred to as “contemporaneity” that present moment in which time has been spatialized and seems to have stopped its inexorable forward path. However, if you think about it, contemporaneity, understood in this way, would be rather the last period of Western history; the moment in which this history, conceived as a hegemonic and central history, collapses and its gears are broken. What we are witnessing, rather, is the jam of the discursive tools with which Western humanistic disciplines have thought about the world and history. It is the crisis of a whole model of knowledge that has been created through a conception of the world based on the pre-eminence of the West and its history over the rest of the globe. When we enter a period like the present one and demonstrate the importance and centrality of other lines, other modernities, other histories, other concepts and categories, the whole historical discourse, with its tools of analysis, collapses.

Perhaps, it is the art world that has best understood this crisis and has been able to reflect on the structure of the time of the present. In a way, the art of the last decades has become a kind of laboratory to think about the different ways of living and thinking today. Concepts that have emerged within it as “Multiple Modernity” (Keith Moxey) (2013: 11-22), “Altermodernity” (Nicolas Bourriaud) (2009) or “Postcolonial Constellation” (Enwezor) (2008) that have precisely in common an awareness that the world must be thought of as multiple and plural, both spatially and chronologically. The time, histories and ways of experiencing them are manifold and do not walk in a single direction, but must be understood through heterochrony –diverse temporal lines that always work at once, in conflict, in perpetual motion– and the anachronism –discontinuities, jumps, non-successive times that twist on themselves.

The present is thus composed of an amount of times in motion, of pasts that are not just leaving and futures that never came. However, this heterochrony of contemporary experience is constantly threatened by the monochronic of the hegemonic chronological regime that governs globalization. A globalization that is basically a process of large-scale chronological synchronization with the time of capital and Western technology, a reduction of all time at the time of technological progress –a time, which if we think about it, is still the time established in Western modernity.

It is precisely in front of that unique time of technology and globalization, in front of which a whole face of the contemporary art tries to present modalities of resistance through complex temporary experiences. Take, for example, Ursula Biemann’s video-essays, which examine the different temporal regimes of technology, labor, control, exploitation and migration across the globe. Or in photographs of Zoe Leonard’s project Analogue (1998-2007), showing the routes of goods from the first to the third world watching how the times and memories of the advanced and obsolete are redefined in each spatial context. Or even in the works of Xu Bing about the impossibility of translation and temporary experiences between East and West, through working with archetypes of Chinese tradition.

There would be almost infinite examples that could be brought to bear on this type of art. But all of them are characterized by time as a working material, a time that can be opened and altered, a time capable of breaking the global rhythms of circulation of capital and introducing chronologies and temporary experiences that tear and fracture any hegemonic temporality. These are, ultimately, “counter-chronologies” that turn the established experiences of power around. Maybe today this is the only thing that the advanced arts have in common: the power to subvert the temporary experience of power.

References

Agacinski, S. (2003). Time passing: Modernity and nostalgia. New York: Columbia University Press.

Bal, M. (1999). Quoting Caravaggio: Contemporary art, preposterous history. Chicago, Ill: University of Chicago Press.

Bourriaud, N. (2009). Altermodern: Tate Triennial Exhibition of Contemporary British Art. London: Tate Publishing.

Bourriaud, N., Herman, J., & Schneider, C. (2005). Postproduction: Culture as screenplay: how art reprograms the world. New York: Lukas & Sternberg.

DeLillo, D. (2010). Point Omega: A novel. New York: Scribner.

Didi-Huberman, G. (2005). Confronting images: Questioning the ends of a certain history of art. University Park, Pa: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Doane, M. A. (2002). The emergence of cinematic time: Modernity, contingency, the archive. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

Enwezor, O. (2008). “The Postcolonial Constellation: Contemporary Art in a State of Permanent Transition”, en Smith, T., Enwezor, O., y Condee, N., eds., Antinomies of Art and Culture: Modernity, Postmodernity, Contemporaneity, Durham, Duke University Press, pp. 207-235.

Foster, H. (1996). The return of the real: The avant-garde at the end of the century. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press.

Fried, M. (1998). Art and objecthood: Essays and reviews. Chicago [Ill.: The University of Chicago Press.

Greenberg, C. (1961). Art and culture: Critical essays. Boston: Beacon Press.

Hernández-Navarro, M. A. (2012). Materializar el pasado: El artista como historiador (benjaminiano). Murcia: Micromegas.

Krauss, R. E. (1977). Passages in modern sculpture. New York: Viking Press.

Kubler, G. (2008). The shape of time: Remarks on the history of things. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Lee, P. M. (2004). Chronophobia: On time in the art of the 1960’s. Cambridge, Mass.: M.I.T. Press.

Martin, J. (1999). “Returning the gaze: The American response to the French critique of ocularcentrism”. Perspectives on embodiment: The intersection of nature and culture, 110-114.

Mignolo, W. (2012). Local histories/global designs: Coloniality, subaltern knowledges, and border thinking. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Moxey, K. P. F. (2013). Visual time: The image in history. Durham: Duke University Press.

Negri, A. (2006). Fábricas del sujeto/ontología de la subversión: antagonismo, subsunción real, poder constituyente, multitud, comunismo. Madrid: Akal.

Rosa, H., & Trejo-Mathys, J. (2013). Social acceleration: A new theory of modernity. New York: Columbia University Press.

Ross, C. (2012). The past is the present; it’s the future too: The temporal turn in contemporary art. New York: Continuum.

Smith, T. (2010). “The state of art history: contemporary art”. The Art Bulletin, 92(4), 366-383.

Virilio, P., & Polizzotti, M. (2006). Speed and politics: An essay on dromology. Los Angeles, CA: Semiotext(e).

* This text is integrated into the R & D project Temporalities of the image: heterochrony and anachronism in contemporary visual culture, Ministry of Economy and competitiveness, HAR2012-39322. An earlier version was published in the journal Puentes de crítica literaria y cultural, 4, 2015, pp. 68-77